History

70mm film made its debut in 1899 when Kodak invented the 116 format. This was a spool format meant to produce large negatives (6.5 x 11cm, 6 exposures per roll) for consumer cameras. It predates the popular 120 spool format by two years. 116 was designed specifically for large negatives, while 120 was designed to support a range of frame sizes for more compact cameras.

In 1932 Kodak created the 616 format, which used the same film, but on a narrower spool, enabling cameras to be slightly more compact. Both formats utilize a film strip about 36 inches long.

616 (left) and 116 (right) spools. Photo courtesy of Bryan Chernick

While Kodak officially discontinued both formats in 1984, they fell out of popular use long before that. However, modern 70mm film can be re-spooled into 116/616 for use in these cameras today.

The modern 70mm format was developed in the early 1950s for military reconnaissance. Prior to that period, most aerial reconnaissance was accomplished with large format roll film. This produced maximum recording resolution, but required massive cameras and magazines, with significant power requirements, expenses lenses, etc. Improvements in film emulsion made it possible to shoot in medium format starting in the 1950s. Because Kodak was already manufacturing 116/616 format 70mm film stock, and it was the largest medium format film they manufactured, they chose this as the film width for this new bulk-roll format. This new, professional format was just called "70mm" to differentiate it from the consumer "branded" 116 and 616 formats. Because the new 70mm format eliminated backing paper in favor of a daylight spool to daylight spool or cassette to cassette system, it could be manufactured much more economically in a system that required reloading only very infrequently. It began as 100 ft or 250 ft rolls of double perforated (“Type I”) film that would be loaded directly into aerial cameras. Soon, however, terrestrial photographers saw the advantage of longer rolls of film.

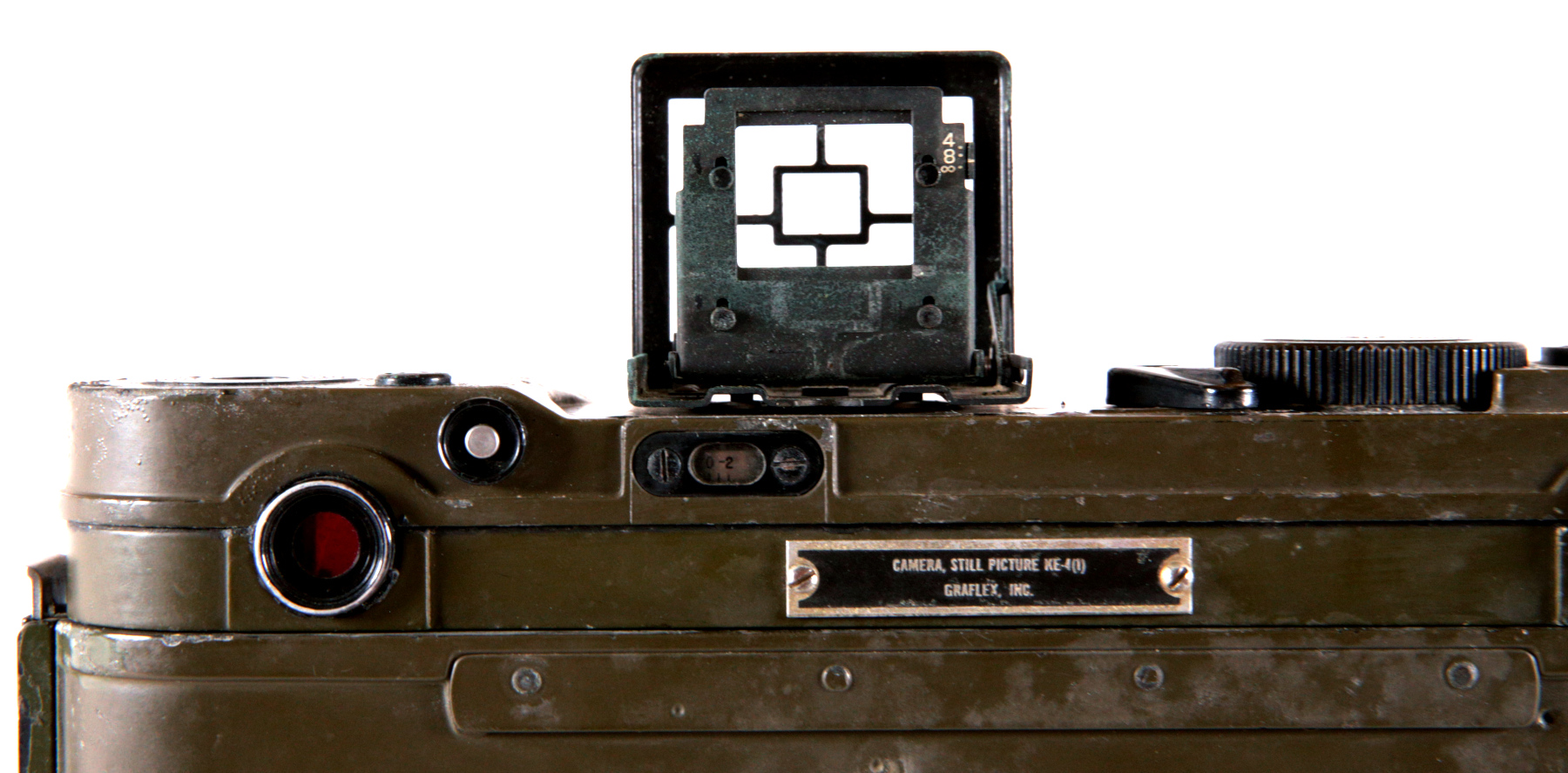

Graflex KE-4 Combat Graphic 70

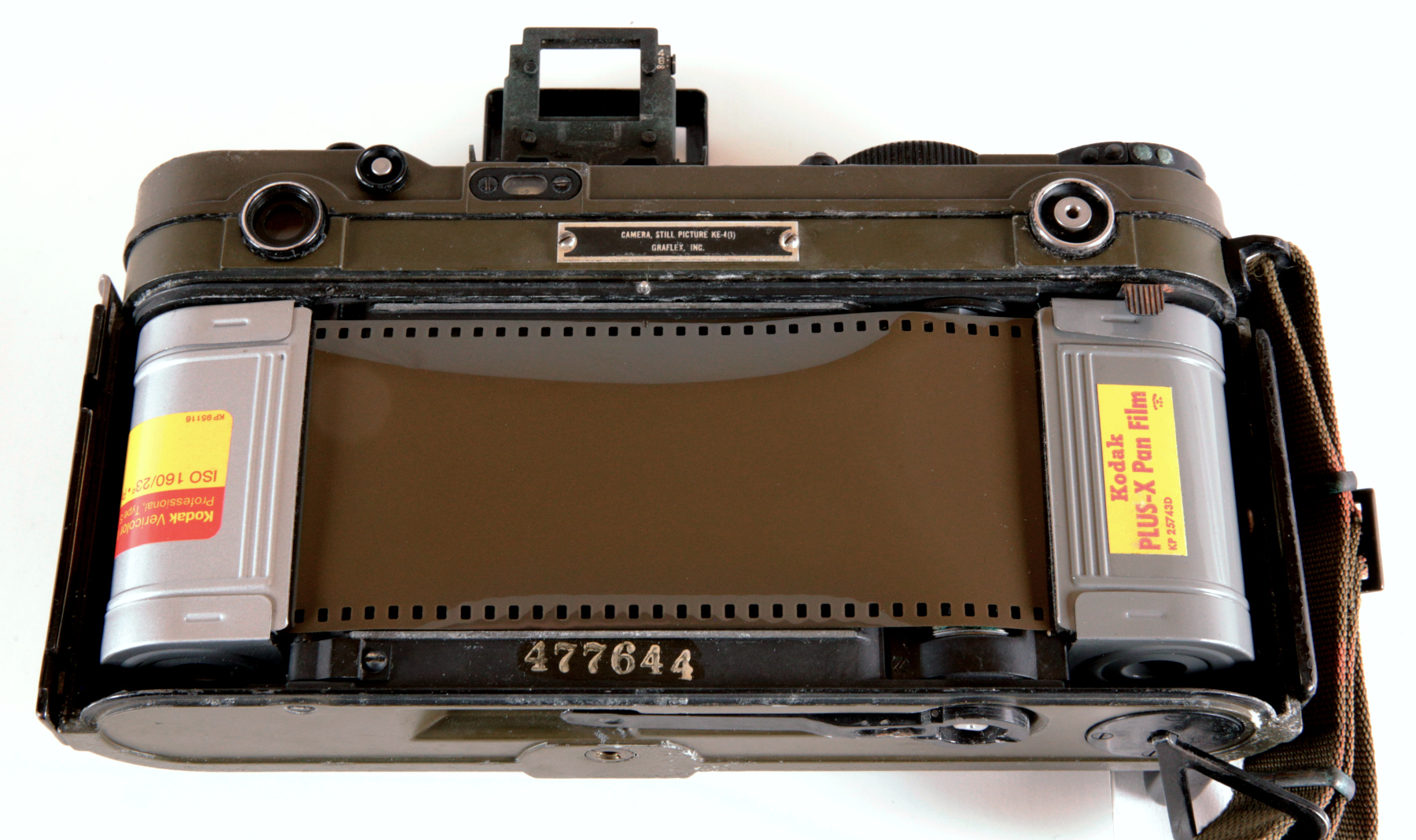

Perhaps not surprisingly, given that 70mm film was developed for military aerial use, the US Army was the first to make use of it in ordinary cameras. When the Army commissioned a medium format combat camera in 1953, Graflex designed it to use 70mm film. Its designer, Hubert Nerwin, had been smuggled out of Germany (where he had been the lead designer at Zeiss Ikon) after WWII via Operation Paperclip. Because Graflex was a US military contractor they were eligible to employ him. Nerwin had designed the famous Contax rangefinder, and applied many of its design principles to this larger camera.

It is likely for this camera that Kodak (also a military contractor) developed the 70mm cassette system. The resulting camera was the KE-4 Combat Graphic. It remains the only known example of a handheld camera (as opposed to a removable back) that natively shoots 70mm film.

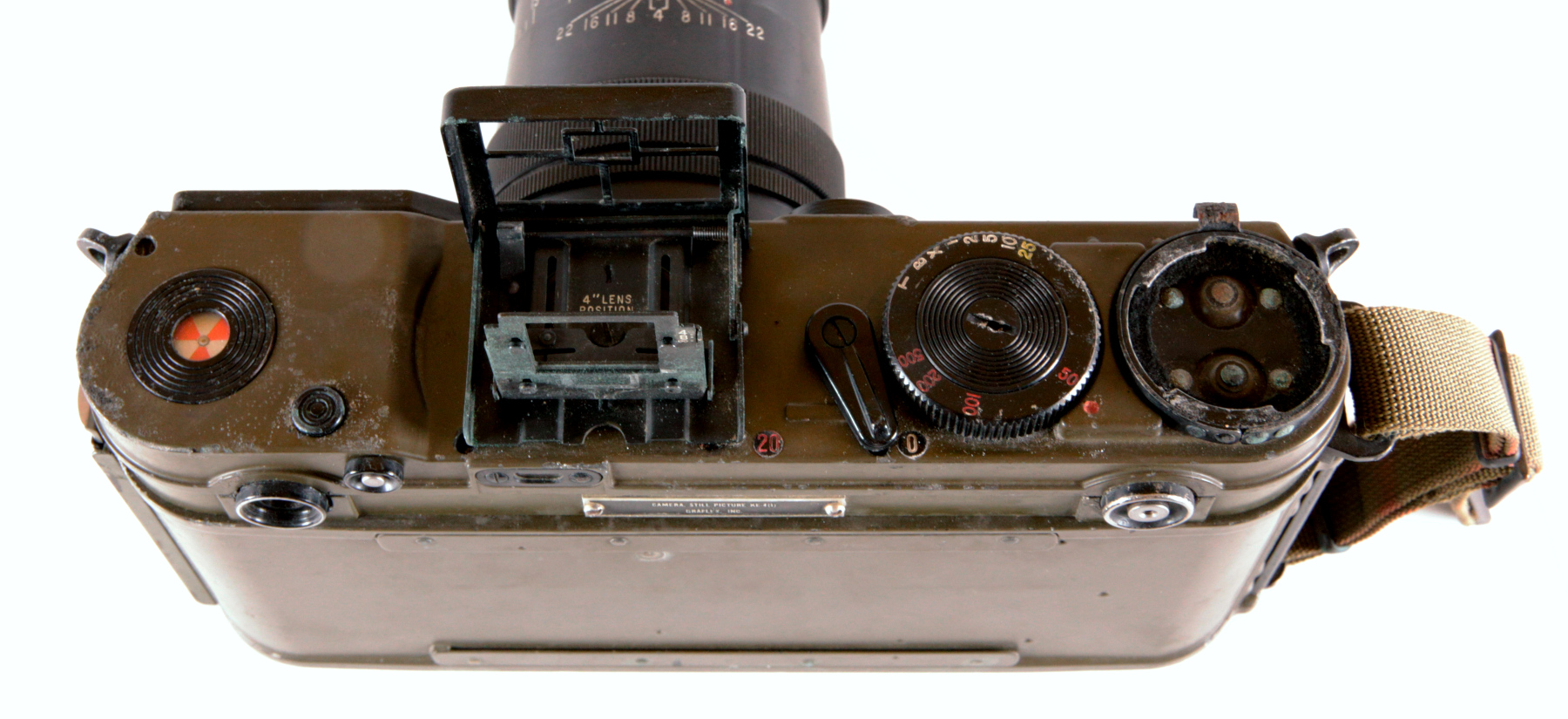

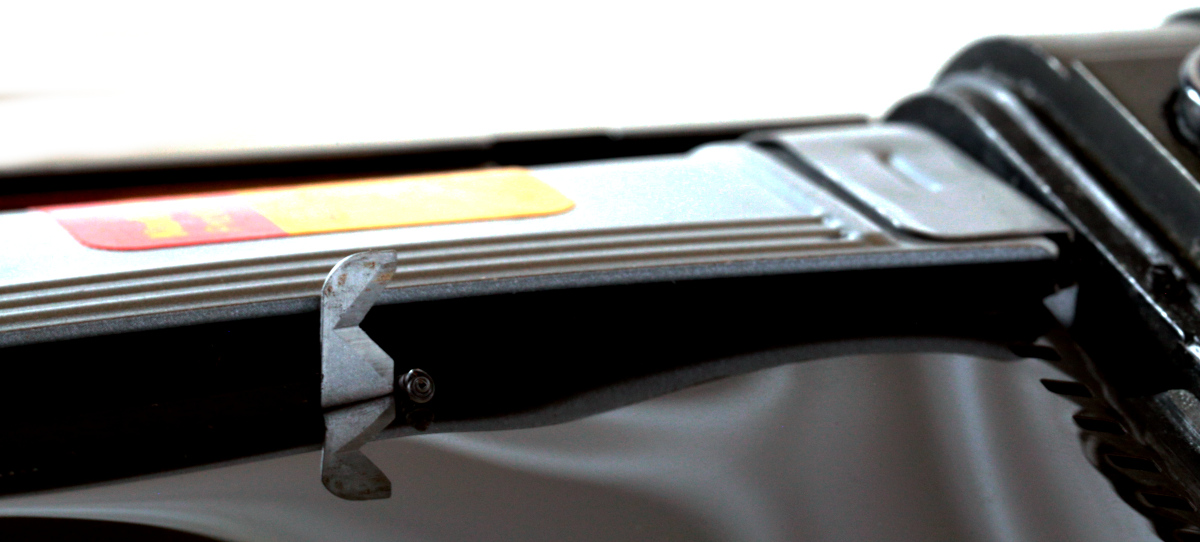

70mm makes sense as a format for high-end photos taken in active war zones, when there isn’t often time to reload film. The camera contains a built-in knife cutter, allowing the film to be cut for developing at any time, even when no scissors are handy! As mentioned in the Introduction, this is an excellent feature of 70mm: the film can be cut at any point, and the remaining film in the camera can be easily fed into an empty cassette to continue shooting.

Given the fast loading cassette system, the high detail of medium format, the long roll format for many exposures without reloading, and the ability to cut mid-roll to develop at any time, the KE-4 harnesses many of the advantages of the 70mm format for wartime needs. This camera designed during the Korean War, but I don't believe it was deployed there before the armistice in mid 1953.

The KE-4 includes a built-in range finder, sport finder for rapid composing, and attachable flashbulb unit. The camera is quick-advanced using a pop-out crank on the bottom.

It uses a variable-opening cloth focal-plane shutter and shoots a standard 6x7 frame. Given its purpose as a combat camera, its emphasis on more on distance shooting than close shooting. It came with three high-end lenses, all made by Kodak: a 4" (102mm), a 6" (127mm), and 8" (203mm) lens. These are on the long side compared to comparable medium format cameras for portrait, street, and studio use. About 1500 of these were manufactured and deployed in the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Production ceased in 1957.

Beginning with the Gemini program in the mid 1960s, NASA used 70mm film for all of its handheld space photography. The space agency used a custom 70mm magazine fitted to a Hasselblad wide angle camera. Its purpose was to take shots of the Earth's surface from orbit. For the Apollo program, NASA used a set of specially modified Hasselblads 500EL cameras, outfitted with Haselblad's new 70mm backs. The special version used on the Moon's surface was called the Lunar Data Camera.

NASA's Lunar Data Camera. Photo credit unknown.

NASA wanted to be able to take as many photos without reloading as possible, and thus contracted with Kodak to produce thinner-base films, so more could be loaded on their 70mm cassettes. Kodak made a special black and white negative thin-base film and a special thin-base Ektachrome film for NASA. The BW film was thin enough for 200 6x6 exposures worth to be loaded on one standard 70mm cassette! Kodak's color film could cram 160 exposures in one cassette.

Perhaps the most famous and influential photograph of all time, "Blue Marble," was taken on 70mm Ektachrome during the Apollo 17 mission. It was the first photograph to depict the whole earth.

-web.jpg)

"Blue Marble" from NASA

While NASA, Hasselblad, and Kodak were orbiting the planet and exploring the Moon in 70mm, Earthbound photographers were also making heavy use of the format.

At the end of the 1950s, Beattie Coleman, an American company based initially in California, began to release a series of products aimed at high-volume portrait photographers. They called their line of cameras “Portronic.” These cameras were large, heavy, and inflexible, but did one thing really well: shooting high quality portraits very quickly!

The most common Portronics were twin lens reflex cameras, with a taking lens below and a viewfinder lens above, with a built in viewing hood and parallax correction. A ground glass could also be inserted in the back of the camera for initial setup. Once set up, the camera wasn't meant to be moved; the subject would be positioned in relation to the pre-existing frame.

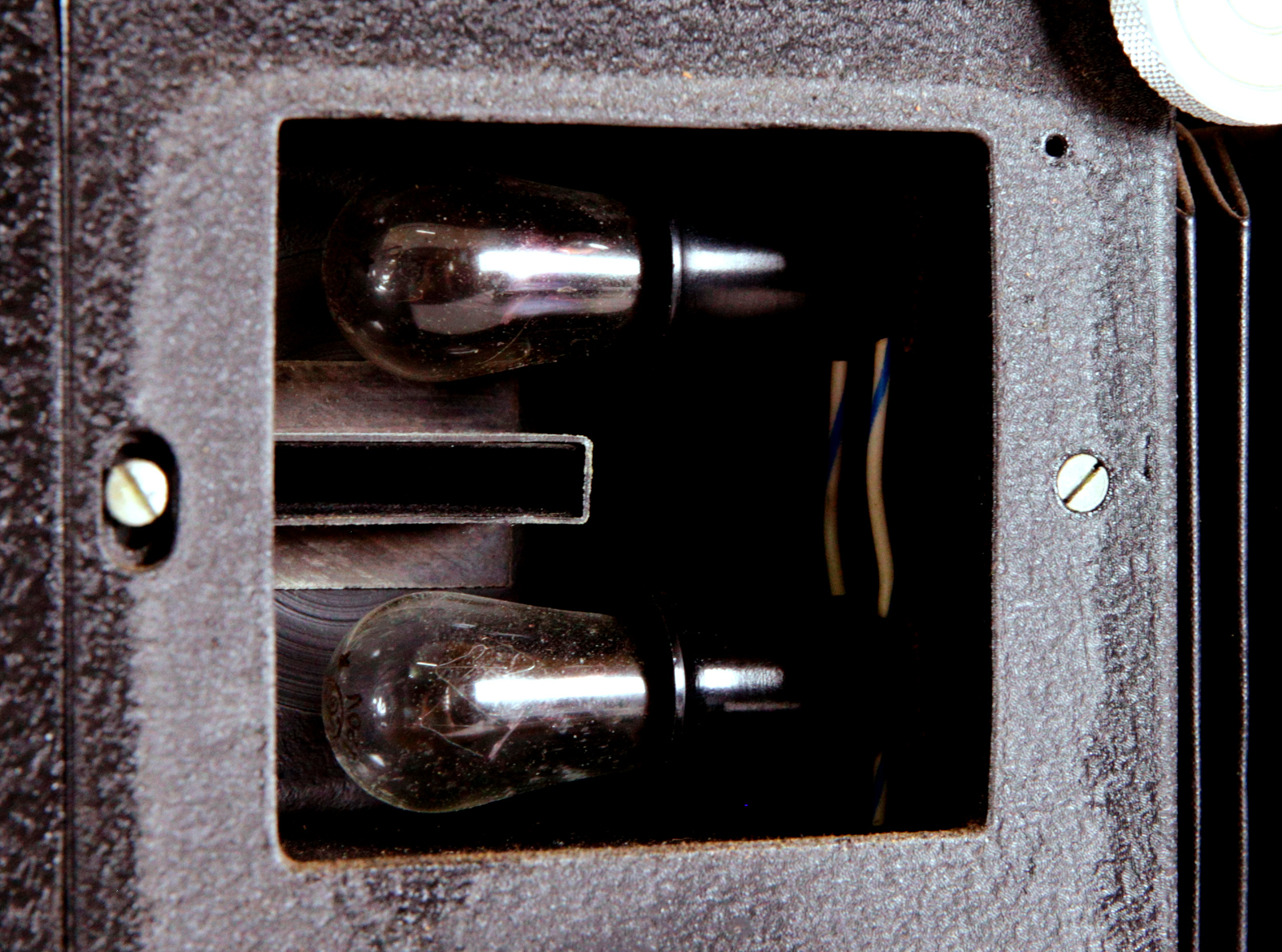

Portronics are all electronic: shutter and film advance run off AC power. A unique feature was the ability to record an “info card” on film between the portraits. The photographer could write identifying information on a small card and insert it behind a retaining plate on the side of the camera.

An info exposure chamber inside the camera illuminated the written portion of the card with special lamps, then reflected it onto the film. This exposure happened simultaneously with the portrait exposure. This is how photographers matched their customers to their rolls of hundreds of photos once they came back from the lab!

The enormous magazines, or “bricks,” on these cameras were motor driven and accepted full 100ft spools of film. They generally shot the 645 format, which would enable 425 frames per roll.

These cameras, and similar ones made in later decades by another company, CameraZ, ruled high-volume backdrop-driven portraiture for decades, generating a thriving market for portrait films in 70mm (see 70mm Films).

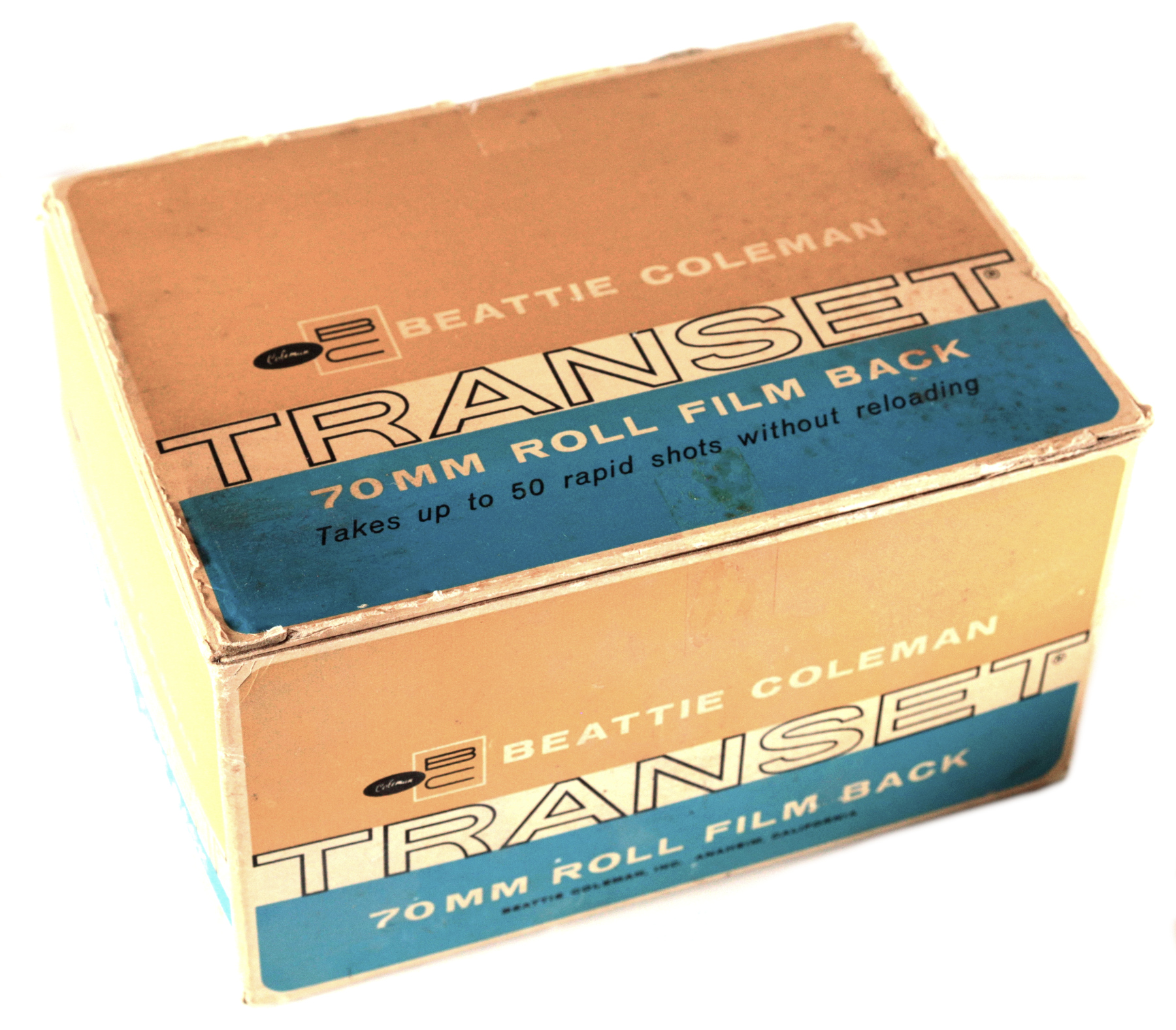

Beattie Coleman also created a 70mm film back for large format

4x5 cameras, designed specifically for portrait photographers who had legacy large format

equipment and

have the budget or volume needs of a Portronic camera.

70mm film use reached its peak in the 1980s, when it was used by military, amateur, and professional photographers alike. The most advanced film-based aerial reconnaissance camera system ever developed was released in 1986. It consisted of a camera that would take 3 photos simultaneously to be reconstructed into a 3D image. Zeiss created their most legendary lens, supposedly the sharpest lens they ever developed for medium format, the legendary S-Topar A2. (Mercury is the only camera in the world other than the original aerial camera that can natively accept this lens.) At the same time, Bronica, with a camera lineup aimed at wedding photographers, released 70mm backs for them.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, these professional uses of 70mm continued unabated, while amateur use lessened as more photographers adopted the 135 format to save money and weight. Thus as medium format lost popularity to 135, the low end of the 70mm market dried up, while the high end continued.

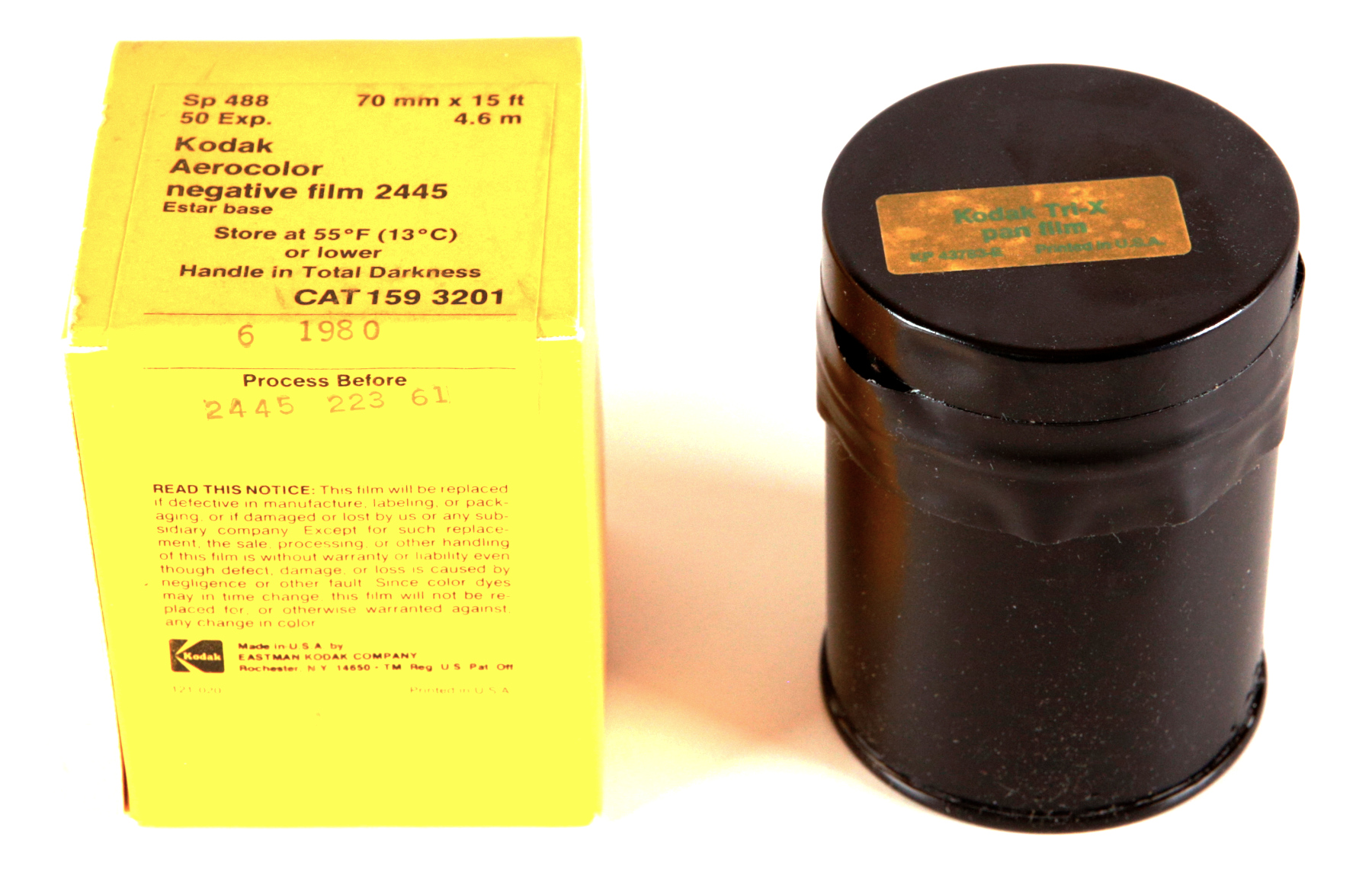

The real blow to 70mm film came with the widespread adoption of digital. Professional portrait photography went digital around 2005. Kodak stopped regular production of 70mm portrait film (Portra, Tri-X, BW400CN, etc.) in 2008. Konica and Agfa stopped producing their portrait 70mm film around the same time. In the aerial film market, digtal captured the low end and the high end continued with larger (usually 5" or 9.5") film. Agfa produced their 70mm aerial film for a few more years. Their final stock was licensed by Rollei and produced until 2019 as “Rollei 400 Professional.” With its discontinuation, only Ilford's HP5+ is still produced (see the 70mm Film page).

With the cessation of professional use of 70mm has come a renewed interest in the format by advanced amateurs. As interest in shooting film in general, and especially medium format, has skyrocketed in the past few years, quite a few photographers are actively shooting 70mm. The rest of this Guide is for those of you who would love to start reaping the benefits of this amazing format, but don't know where to start!